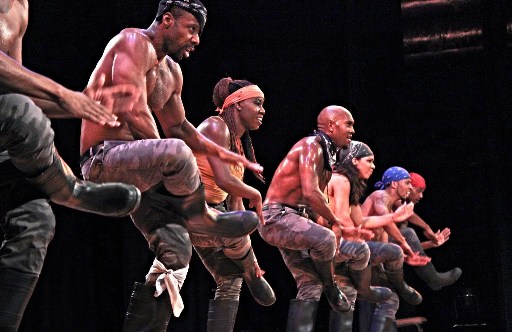

Leadership Corner: C. Brian Williams, Founder/Executive Director, Step Afrika!

Photo courtesy Step Afrika!

C. Brian Williams hails from Houston, Texas, and is a graduate of Howard University. Brian first learned to step as a member of his fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha in 1989. After living in Africa he began to research stepping, exploring the many sides of this exciting, yet under-recognized American art form and founded Step Afrika! in 1994. Williams has performed, lectured and taught in Europe, South and Central America, Africa, the Middle East, Asia, the Caribbean and throughout the United States. He is a founder of the historic Step Afrika! International Cultural Festival in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Brian has been cited as a “Civic/Community Visionary” by NV Magazine and “Nation Builder” by the National Black Caucus of State Legislators. He is featured in Soulstepping, the first book to document the history of stepping, and several documentaries discussing the art form. Brian was also cited by Washingtonian Magazine as “40 Under Forty to Watch.” He is a recipient of the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities Artist Fellowship; the Mayor’s Art Award for Innovation in the Arts; and the 2011 Pola Nirenska Award for Contemporary Achievement in Dance.

Dance/USA: Introduce yourself to us please. You were a marketing major at Howard University and had no intention of running a dance company for 20 years. Yet, here you are.

Brian Williams: I like to say I entered the dance world as a traditional artist. Stepping, when I first learned about the art form, was largely folkloric, a traditional dance that you couldn’t learn in a studio but instead, had to access only through the lens of a community, and a very particular community at that. I became aware of stepping and its potential after I pledged the fraternity, learned the traditional steps of my organization, and participated in several step shows on college campuses. For some reason, I recognized stepping for its artistic and performance possibilities even then. The art form was something I felt more people should have access to …. At that time, in 1989, stepping wasn’t widely recognized, even by the African-American community, let alone the broader American community. It was a somewhat “private” tradition seen only on the college campus. So I said okay, let’s look at this art form and see what else we might be able to do with stepping.

D/USA: You wouldn’t call it vernacular or street?

BW: Not at all. Stepping to me will always be a folkloric or “ritual” dance: a dance not originally designed for the stage and done to serve a particular role or function for a community. Stepping started on the college campuses, created by African-American college students who were first and foremost, members of organizations that were dedicated to scholarship and community service. Stepping is therefore an artistic “by-product” of these organizations and I try never to forget that in my work with Step Afrika! I did begin to see, however, that there was potential for the art form to develop. So when I graduated from college in 1990,

I started looking for opportunities to take the art form to some new and hopefully exciting places.

Moving to Africa in 1991 really changed everything. At the time, I was more interested in theater, performance, Shakespeare, poetry. So I was looking for performance opportunities while living in Lesotho, a small country surrounded by South Africa. I lived there while South Africa experienced major turmoil and transitions: Mandela had been released, there was violence all around and here I am in this tiny Mountain Kingdom watching all of this happen. In Lesotho, I first came across the South African gumboot dance. I saw this young boy making percussive sounds with his “gumboots” and it reminded me of my college step show days. I was completely shocked. I asked my students to teach me about their dance form and I, in turn, taught them about stepping. I enjoyed that exchange and their response. So I thought, ‘We should do something with this’ That’s where the seeds of Step Afrika! were planted and to this day it’s still about international exchange and cross-cultural partnerships. That’s just what the company does at its core.

But turning this idea into a functioning organization? That’s a whole other conversation…

D/USA: Let’s look at Step Afrika! organizationally. Today your budget is $1.5 million. Your dancers have an 11-month contract and tour nearly constantly. That’s a success. But you were an “outsider” in the arts, coming from business school not a dance program. You didn’t know a thing about running a dance company. What did you have to learn and how did you do it?

BW: I didn’t know about 501(c)3s, knew nothing about grants.

But here’s the thing: First came the artistic opportunity, then came the business. For me, the question was, ‘How do I make this happen? What do I need to do and what are the first steps?’ I wanted to share stepping with the world.’ Making money really wasn’t the idea. If money had been the primary motivation, then I am sure I wouldn’t have gotten too far. Instead … it was the idea to step all across the continent of Africa, learn traditional dances, and explore the nexus between stepping and traditional African culture that really motivated me to launch Step Afrika! The question became: ‘How do I make that happen? And what are the opportunities?’

That’s when I started to explore the non-profit model — the world of grant-making, the world of donations, which was all very new to me. It’s important to say because for me the issue was: how do I find the money to support this work… not how do I make money.

Photo courtesy Step Afrika!

D/USA: From a business school perspective you had a product idea and a product development, so why did you choose to go non-profit and not for profit?

BW: Again, making money has never been my primary goal. If so, I probably would have gone directly to corporate America after graduation versus accepting a fellowship to teach small-business skills in Southern Africa. Instead, I launched Step Afrika! because I wanted to connect with the world around me through an art form and dance tradition I deeply loved. Plus, I enjoyed performing, learning other dance traditions, and exploring cultures. Although I am very grateful for my business background — I like to brag that I have never run a deficit in my 20 years in the non-profit arts world — I would have been just as comfortable studying cultural anthropology. The non-profit model really supports mission-driven work. So I feel that it was a perfect model for Step Afrika! and my vision for the company. I am really glad that I decided to go non-profit versus for-profit.

D/USA: Most of our dance leaders don’t come out of business school, so if you had taken the business route and commodified the business you could have gone in other directions, maybe franchising or something else.

BW: Maybe I would have tried to make a hip hop DVD or would have tried to teach step in a commercial dance studio. But that’s never been my or Step Afrika!’s purpose. We are truly mission based. The commercial opportunities — that’s for others to take advantage of. That’s not really Step Afrika’s role. Our role is to teach children, to create a platform to exchange and share the art form, and to expand its artistic possibilities. Our purpose is not to sell something just for profit.

D/USA: So take us further in your journey.

BW: One thing that has made a great difference for me is this: capacity building programs for artists and arts organizations. Those programs have been huge for Step Afrika! — absolutely essential. Without the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities and their work on behalf of artists and several other programs, I would have never acquired the skills necessary to survive in the arts world. The capacity-building programs I encountered encouraged consultants to descend upon your organization and tell you what needs to happen in terms of taxes and grant making, human resources, engagement. That’s where I learned about developing the organization. Even with my business skills, Step Afrika! would have never grown if I didn’t have a series of talented consultants to say, “Here are the resources and you should do this.”

That’s where artists really struggle because we don’t often get access to skilled business consulting. Or we are resistant to it for obvious reasons. For Step Afrika! such programs made all the difference. The ones that are really good should be replicated and invested in because they help artists build their businesses; support their artistic work; and encourage them to become integrated partners in their communities.

Look: All most artists want to do is create work. They need to get the resources to do that. We can’t be experts in all areas, so we need support to grow the other side of our businesses. Arts organizations are all real businesses.

I had to learn, for example, how to manage human resources … and this remains a work in progress! I’m not a human resources manager. That’s a specific skill set, but there are people that can help you do that. For example, I worked with an HR consultant through a capacity-building program, and, to this day, when I need to, I can reach out to her. She has helped me tremendously.

D/USA: These are businesses and time, too, is a commodity. What’s your day’s pie chart look like? How do you spend your time: development, artistry, human resources?

BW: I have a couple of thoughts on that. First of all, a work day in the non-profit arts is 24 hours. That’s what we signed up for. In those 24 hours, about six to eight hours are for sleep. I do need to sleep to take care of myself. In the remaining 16 hours, I would say, management of the team takes a lot of that. Just day-to-day management and task making is what I’m doing to make everything else happen. I have a development director who does that as her sole focus. To be a true executive director, I should probably focus more on development, but I think a lot of arts organizations and their founders didn’t get into this to strictly be fundraisers or strictly be development people. So I’m very careful not to let this part of the work overtake me. I know that the key to fund-raising is in relationship building and I could do it very well if I focused more on it, but that’s just not what I’m here to do strictly. I’m here to do the work and I want to be part of the work.

I have an artistic director now, and I have tried to lay that position out clearly. What I’m thinking about artistically is not what happens in the studio, I’m thinking artistically about the big picture collaborations we do, big picture artistic opportunities. Although I didn’t choreograph Symphony in Step [an evening-length collaboration with a symphony orchestra], I was the one who produced that project. I liased with the composer and we went back and forth and I provided him with artistic feedback in the writing and structuring of the music. I view myself more as a producer now than a director in the studio.

D/USA: I’ve heard from other AD’s, particularly when dealing with large collaborations, they often step into the producer role of managing the process and not being as actively connected to the day-to-day work in the studio.

BW: I hope people respect that as an important artistic transition. One thing I’ve often heard because of my business background and training is that I’m less of an artist, because I have this business understanding. My AD, for example, might want unlimited studio time [but] that’s not really realistic. No one can sit in the studio for days and days. Step Afrika’s struggle has always been that we never get enough studio time because our touring schedule is so rigorous. We’re on the road about nine months a year.

What I’m saying is that I love that Step Afrika! spends more time performing than rehearsing, although sometimes I do wish that we had a little more time to rehearse.

D/USA: That makes sense. No deadline, no finished product.

BW: This environment is challenging. And, unfortunately, there is not a lot of funding out there that allows artists — especially a dance company with 11 full-time artists — to play in the studio for extended periods. Earned revenue is very important to Step Afrika! so my three agents and I are constantly looking for ways to keep the company performing.

It’s also one of the reasons why I first decided to do multi-night engagements like our upcoming 20th anniversary Home Performance Series in Washington, D.C. Why doesn’t dance have more multi-night runs? When we started this series over eight years ago, it was a game changer for Step Afrika!

D/USA: In what sense?

BW: For one, the work got better. I used to hate rehearsing hours and days for one or even for two nights of performances. It was simply so much time in the studio for one shot on the stage. I needed at least five shots, maybe six, preferably twelve so that work can develop and new and existing choreography can get better, and artists can become stronger performers. My goal is: Spending more time onstage with the work instead of always preparing and only doing the work once.

Now our dancers have an 11-month contract and we’re on the road for at least nine months out of the year. We tour so much and everybody always wants something new, new, new. So we struggle because we’re on the road so much that we have to balance the demands of an aggressive touring schedule, which is what keeps the company alive, and the need to create the new work. We can only do that in the studio and no one pays for us to be in the studio. There’s not enough general operating support or individual donors to support that studio time. Touring becomes the way we support the creation and rehearsal of new work.

I would say two months are dedicated somehow but not exclusively to studio time. We have to be very targeted in that time to create new works.

Photo courtesy Step Afrika!

D/USA: For some companies international touring is a holy grail, to broaden dancers’ experiences and gain an international reputation.

BW: We’ve been very lucky with international touring, but it’s still an underdeveloped part of our work. I think we could do a lot more, particularly in Europe. Most of our touring internationally has been through the U.S. State Department and that’s a very important opportunity for Step Afrika! But I would like our international tours to become more peer-to-peer in the future, so that we go into theaters and perform much like the commercial music industry. We want foreign presenters to be interested in having Step Afrika! perform abroad … versus having the State Department or an embassy subsidize us to perform.

In general, I think there’s a market for American dance, but we haven’t reached it yet. I do think we have to be more realistic in our fees, knowing all the costs for touring these days, and how hard it is for presenters to make costs work. So we need to ask ourselves, what do we need to do to make American dance attractive for them.

Besides capacity-building, the other game changer for Step Afrika! was improving the agent-artist relationship. Having an agent changed everything. We got our first agent in 2000, only six years after I founded the company. That agent-artist partnership changed the whole conversation. I could focus on the work; the agent focuses on finding business for the work. I’ve had the same agent for 15 years and we’ve since expanded to three agents, which allows us to create a calendar that we can run 11 months a year and pay our dancers full time. It’s the only way. No agent, no Step Afrika!

Our first international tour was very happenstance. The cultural affairs director from the U.S. Embassy in Mozambique came across our website and wanted to bring us in for a dance exchange because they had a dance form that was very similar to stepping. I think they gave us $1,000 and we went because we were already in South Africa. The money we generated really only covered the costs of the tour, not overhead. For me doing an international tour is about the opportunity to perform and exchange. So that business opportunity creates that artistic opportunity.

I would encourage artists to decide where and when they want to go and what they think they could bring and pitch the embassies themselves. Those cultural affairs officers in the embassies abroad are looking for programming and work that will enliven this U.S. cultural exchange and what diplomats call “soft” diplomacy. Every city and consulate has its own budget and own Public Affairs section. Do understand that it’s a long engagement process, a year or more, before you actually get there.

D/USA: Tell me about moving your dancers from part-time to full-time.

BW: I moved my dancers from part-time to full time, almost ten years ago. Before that, I worked full-time for Step Afrika! but the dancers were part time and, of course, worked other jobs. I wanted to simply guarantee a salary so we could get more bookings and scheduling would be easier. Now it wasn’t an incredible salary when I first began, but guaranteeing a salary was a business decision. I looked at my income statement and calculated how much I had paid the artists in the previous year. I think it was about $20,000 in 2006. I realized I could guarantee them that same $20,000 up front as salary, rather than per performance. Once the dancers became full-time, I could basically do a show a day, every day without scheduling problems! I could guarantee both dancers and a very strong performance quality. You know, the only way to create consistent work is to work consistently. Bookings went up incredibly as a result and next I hired more dancers and considerably increased salaries.

D/USA: If you weren’t doing this, what would you be doing?

BW: I have no idea.

I always wanted to be in the arts. I’d probably be acting. I always wanted to be in the theater. I’ll never forget I was auditioning for a touring Shakespeare company. I also had a full-time job at the time and when I got down to the final two people for the audition, I said to myself, ‘Am I going to do this? Quit my job and live on buses touring the country doing Shakespeare?’ I said, ‘I don’t think so.’ I just didn’t feel like that’s what I needed to do.

Then just a few weeks after the audition, I traveled to South Africa. It was 1994 and I worked with Africare, managing some really exciting human resources development projects in South Africa! That year, I met the artists from the Soweto Dance Theatre and six months, later, Step Afrika! was born. If I had quit my job to go on tour with the Shakespeare Company, we wouldn’t be here today.

D/USA: What’s on your wish list for the company?

BW: I’m interested in a really super extended run. I want a month-long run similar to the New York runs. Touring is great, but anchoring yourself in the community and watching the art develop and watching the performers develop and watching the audiences grow … An extended run gives the audiences more chances to see the company and the artists more chances to perform.

I think there are also a lot of collaborations out there for me internationally. I would love to partner with more symphonies through our recently developed work, Symphony in Step, and maybe do a exciting tour of European orchestras with the work.

I also want to tour Africa again, but very aggressively going into villages and deeper into the rural area. I want to get back to the more grassroots stuff we did 20 years ago, taking art and high-quality performances directly to people where they live and work. That would be exciting.

Lisa Traiger edits From the Green Room, Dance/USA’s online journal, and writes frequently on dance and the performing arts for a variety of publications, including Dance, Dance Teacher and Washington Jewish Week.

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.