How the death of professional journalism is impacting the arts in 21st-century America (and what we can do about it)

Photo by Paul Horsley

Editor’s note: This is Part 1 of a two-part article on the changing world of arts and dance criticism. For Part 2 of Art in a Critic Free Zone click here.

By Paul Horsley

“Critics try to make objective judgments based on responses they know to be subjective,” wrote New York Times Co-Chief Theater Critic Jesse Green earlier this year, defending his own negative review of Escape to Margaritaville, a Greg Garcia/Mike O’Malley mashup of Jimmy Buffett songs on Broadway. “So when readers are stung (or just annoyed) by my pans, I remind them that fighting about theater is often the best part of the show.” Jimmy Buffett fans were enraged at Green’s scathing review of the show (which ended up closing earlier than scheduled), and the ensuing debate revealed much about the public’s relationship to arts criticism today: Since any opinion is as valid as anyone else’s, who needs critics?

To be sure, Americans are seeing an erosion of confidence in the authority of professionals in general. Many “Google experts” and those prone to conspiracy theories no longer believe in scientists or physicians, much less journalists. Yet few of us really want to live in a society where government, business and the judicial system run rampant, unfettered by the watchful eye of professional reporters.

Nevertheless, while vigorous debates rage over the erosion of the media’s influence in public affairs — a decay brought on largely by the Internet’s gutting of print’s economic foundations — the disappearance of serious arts criticism in America has caused almost no outcry at all. Outside of arts communities, in fact, it has hardly raised an eyebrow that some 80 percent of professional critics employed by newspapers and magazines 20 years ago no longer make a living at their craft, according to several recent studies, and as confirmed in Scott Timberg’s 2015 analysis Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class.

Tim Mangan, photo by Eric Stoner

For theater, music and the visual arts, the situation is harsh enough — the number of full-time classical music critics, for example, has dropped from nearly 200 in the 1980s to fewer than a dozen today. Responsible discourse on dance, which is notoriously difficult to write about by its very nature, has been especially hard-hit. “When I started here [in Boston] in the 1980s, there were five working dance critics in the city of Boston,” said critic and scholar Debra Cash, who now serves as executive director of Boston Dance Alliance, at an Arts Fuse forum For the Love of Arts Criticism held in Boston earlier this year. Today, she added, there remains not a single full-time critic in all of Greater Boston, a metropolitan area of 4.8 million citizens. And that, said Cash, is “a very, very dangerous situation for those of us who care about the seriousness with which we take our art forms.”

Boston is hardly alone in this “dance drain,” which began as a trickle in the late 1990s, became a flood in the first decade of the new century, and has turned into a tsunami-like catastrophe in the years since. During the past quarter-century on the West Coast we have seen, for example, the elimination of significant dance positions at The Los Angeles Times (Lewis Segal) and the Orange County Register (Laura Bleiberg). The San Francisco Chronicle, which once had two full-time critics reporting on what is generally regarded as the nation’s second-most important dance scene, has reduced its coverage to a sprinkling of freelance articles.

In New York, the dance center of the nation if not the world, New York, the New York Post, Time Out New York and the now-defunct Village Voice have all eviscerated their dance coverage — which included some of the best critical writing in the nation by the likes of Gia Kourlas, Leigh Witchel, Deborah Jowitt and Elizabeth Zimmer. The New York Times reduced its large staff to a lone critic, who plans to retire at the end of this year. And if the Times doesn’t follow through with its pledge to replace Alastair Macaulay with a full-time dance critic, by this time next year, Sarah Kaufman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic of The Washington Post, might well be the “last woman standing.” (At the Chicago Tribune, Lauren Warnecke remains a “freelance contributor,” albeit a busy one, and a few other large newspapers have taken up this less-costly model as well.)

Throughout the rest of the nation, newspapers even in large cities, have eliminated hundreds of arts and entertainment reporters, critics and editors. Many if not most have virtually stopped covering dance altogether — a situation that can create a worrisome crisis for a large ballet company, but can deal a catastrophic blow to smaller and medium-sized companies, which rely on advance stories, at least, to bring about public awareness of their very existence.

The situation in Kansas City, a metropolitan region of nearly 2 million residents, serves as a case in point. During the 1990s and the early “aughts” the arts scene flourished to such a degree that, by general agreement, it was a major engine in the redevelopment of the city’s central districts. Recent estimates by the city and the philanthropic community value the investment in arts infrastructure at well over a billion dollars. This now includes a thriving gallery scene, a vast annex to the world-renowned Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, a dozen viable theater companies and new performing facilities, and the iconic $400 million Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts, which opened in 2011.

The Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts, photo credit: Dance/USA

During this same period the Kansas City Star employed 10 full-time arts and entertainment critics (there was even a full-time jazz critic!), in addition to a veritable army of arts and entertainment (A&E) editors, copy editors and page designers. Around 2005 this coverage began to drop off, and by the summer of 2018 the entire A&E desk had been essentially eliminated. In May, the paper bid adieu to the last of the Star’s full-time critics, nationally renowned pop-music critic Timothy Finn.

Suddenly, professional coverage of the arts has disappeared in Kansas City to a degree that has shocked and alarmed nearly everyone in the community. (Beginning in 2008, a durable and surprisingly comprehensive arts website, grew up mostly as an attempt to fill the void being left by The Star. Largely a labor of love by its editor, Marcy Chaisson, who created a 501(c)(3) for the site, this summer it closed down because of lagging financial support.)

This gradual dissolution of vigorous arts coverage has already become palpable in the local public consciousness, and in the behavior of the non-profits themselves. Major arts groups have grown more conservative, medium-sized groups struggle for survival, and smaller startups are finding it almost impossible to find traction. And though one could debate the extent to which “cause-and-effect” is at play here, many Kansas City arts leaders have commented to me on the extent to which the loss of large Sunday feature stories, in particular — and reviews to some extent — have impacted their ability to reach audiences.

“This is a huge problem in our community and for the arts in general,” said Jennifer Owen, a former Kansas City Ballet dancer who together with her husband, composer Brad Cox, formed a remarkably successful company of her own in 2007, the Owen/Cox Dance Group. “And then there’s the whole idea of quality behind who is writing. Is their opinion really valid, based on their knowledge of the art form? That’s a scary thing: It’s kind of like getting your news from Facebook or social media,” Owen added. “If critics aren’t being vetted for their knowledge or expertise or thoughtfulness or educated opinions, I don’t know what will happen.”

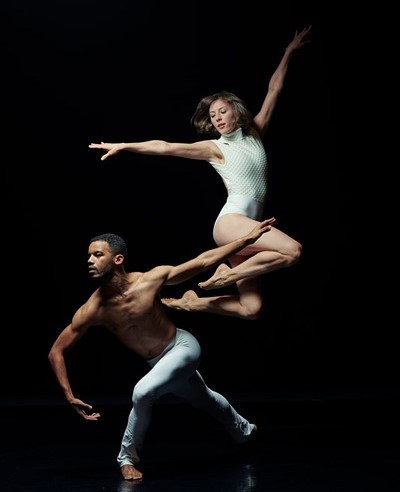

Owen/Cox Dance Group, dancers Emily Mushinski and Tristian Griffin, photo by Kenny Johnson

In a world where online chatter takes the place of professional criticism, Owen said, the public no longer knows where to turn for basic information, much less informed criticism. One recent Owen/Cox program, a collaboration with the city’s venerable Kansas City Chamber Orchestra, included world premieres of works by Owen, and was greeted with warm enthusiasm by audiences and colleagues alike.

The response from what was left of Kansas City’s “arts press”? Utter silence. There was not a single review of the performance, in any medium. “We wanted at least one review, to be able to acknowledge that it happened, and get critical feedback,” said Owen, who has created wildly inventive choreography for large-scale works such as Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Paul Hindemith’s Ludus Tonalis and Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet — all performed with live music.“The audience was so positive. I tried to record everything that people told me, just so that I would have something to put on our grant reports. You really need that.”

To fill the void, Owen’s company has taken to making its own professional videos of performances. The choreographer said that if privately produced videos are inaccessible, future historians writing about 21st-century dance in Kansas City might have to resort to reading grant applications to know that something ever even existed.

But of course an actual record of what it felt like to be in the theater at that moment will remain a gigantic lacuna in the historical record of American culture. “Dance critics have to be ‘people with minds,’ but they also track the history of the most ephemeral art, their theater-going experience serving as memory banks invaluable to the form,” wrote Madison Mainwaring in The Atlantic in August 2015, in a razor-sharp essay entitled, “The Death of the American Dance Critic.”

“It’s widely acknowledged in the dance community that video recordings fail to capture what happens in situ,” she continued. “Such recordings can negate the immediate, visceral response in the viewer, not ‘mindlessness but the state beyond mind that moves us in perfect dancing,’ as [Arlene] Croce once wrote. In writings on dance one finds a unique marriage of head and heart, intellect and intuition. However difficult it is to articulate, this mind-body axis holds significance for everyone.”

Read more on “Art in a Critic Free Zone” in part 2 here. Join us below or on Facebook to contribute to the discussion on this topic.

Paul Horsley is performing arts editor for The Independent, a journal of society and culture in Kansas City. From 2000 to 2008 he was classical music and dance critic for The Kansas City Star, and before that he was program annotator and musicologist for the Philadelphia Orchestra. He has contributed to The New York Times, Dance Magazine, Pointe, Symphony, Musical America, Chamber Music, the American Record Guide, Playbill and numerous other publications. In 2003, he was a National Endowment for the Arts/New York Times Foundation Fellow at the Institute for Dance Criticism at the American Dance Festival. He received a Fulbright Postdoctoral Fellowship for study in the Czech Republic, a Newberry Library Fellowship for research in Chicago, and a German Academic Exchange Grant for study in Berlin and Munich. He holds bachelor’s degrees in piano performance and journalism and he earned his M.A. and Ph.D. in musicology from Cornell University. Find him at kcindependent.com or on Twitter at @phorsleycritic.

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.