By Yvette Ramirez

Yvette Ramirez is a 2021 Dance/USA Archiving & Preservation Fellow. Her Fellowship ran from June-August 2021 and was hosted remotely by DanceATL. Read more about the Fellowship program here. This is the third of three parts of Yvette’s blog. Read Part 2 here.

January 20, 2022: Fellowship Reflections

Lee Harper and Dancers Studio

Something I thought much about this past summer was what archive projects might look like for small-sized, community-based organizations. For my Dance/USA fellowship I worked with DanceATL, a local service organization working with the greater dance community in metro-Atlanta. Typically small in size and capacity, community archives more often than not preserve underrepresented perspectives that are often ignored. Operating outside of mainstream repositories, they have the ability to be shaped by community members who decide how their stories will be told. These spaces represent innovative approaches in archiving that are located in hyperlocal contexts whether it be spatial, temporal, or by affinity groups. One of the strengths of community-based archives are peer networks which practice knowledge and practice sharing, capacity building, and sustainability. In that spirit, I am sharing some observations from my fellowship where I developed recommendations for policies and procedures for my host organization’s community oral history project. If you’re starting a community archival project at your organization, I hope the following provides some guidance.

Encourage an archival practice that goes beyond a project. Center the organization’s mission and, if applicable, current programs as a guide for the archival project you’re working on. This also means allocating ongoing, dedicated time with the organization’s members to present on archiving fundamentals and facilitate conversations specific to the organization. Ideally this time can highlight the expertise and interests held by staff and/or community members, thus encouraging participation and awareness. I give this recommendation with the knowledge that most of the time operating funds are slim for community archives, so I encourage all archivists/archive liaisons to be flexible and creative.

Lee Harper views archival materials during an oral history session.

Learn from other practitioners including those in different fields. Throughout the process, I had to balance archival “best practices” for oral history with accessibility and feasibility for this project. I did this through studying other oral history projects. The archival standard for audio is the WAV file format as it is an uncompressed and thus lossless file. As a much larger audio file, it contains much more detail thus making it more archivally stable than an MP3 file which is compressed and more appropriate as an access copy. Working on the oral history guide for my host organization, remote interviewing was inevitable considering the project’s focus on elders in the community. While Zoom was a platform already used by the organization, it did not meet archival standards as it produced an m4a audio file which is a compressed file/lossy audio. To obtain WAV files, other web based software like Zencastr or Squadcast would be necessary to create high quality audio files, but this would require additional subscription fees. However, oral historians working with cultural institutions undertaking COVID-19 related projects, such as Columbia University or the Smithsonian, have emphasized that accessibility is paramount in their project design and thus they relied on Zoom which allows participants to call via phone in case of lack of internet access or a computer. Another suggestion was asking the narrator to record themselves on a separate recorder and send the file electronically. In essence, there is really no wrong way and this was a reminder to look outwards to what other memory workers were doing and to weigh goals for the project’s final product as well as the organization’s capacity.

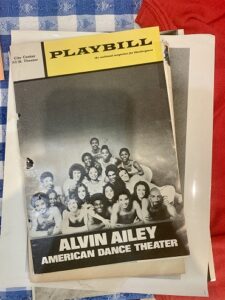

Program for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Break things down – While my project was oral history oriented, auxiliary documents such as photographs and performance programs can also vividly illustrate someone’s life story. Capacity concerns and lack of a physical space were the reasons why my host organization decided only to accept digital copies for their oral history archive. Ownership of a physical item does not equal ownership of the copyright and this extends to a digital surrogate, especially with materials such as publications which are likely to have external creators. Language about copyright can be overwhelming, so it is important that donors have a clear understanding of what they are contributing to the collection. A deed of gift is the main tool used to transfer ownership, copyright, or a license of a record to another entity. In my search for deeds of gift within post-custodial models, unfortunately I was unable to find many examples specifically for digital surrogates. I thought a next best step would be to create a script for organization members to walk donors through the process so both parties can be as informed as possible. Questions centered on:

-

- Description: Can you describe each record you will be sharing with us? Who and where is it from?

- Form: depending on the type of material ask questions accordingly: Do you know who is the photographer/videographer/artist?

- Restrictions: are there any precautions we should take in regards to sharing them or how it’s shared?

- Copyright & License Transfer: Do you own copyright to this?

-

-

- If yes to some materials: it seems like you do have copyright to at least some of the materials so we can share and steward your material in the following ways…

- If it is determined no, ask if they have contact information of potential copyright owner(s).

-

Consider this as a collective investigation between donor and organization member. When it’s time to share records publicly, this will be helpful to evaluate what is most appropriate to share under US copyright law or if you need to do further investigation to get appropriate clearance on who owns rights to what.

Note: The Guide to Clearing Rights for the Performing Artist by The Research Center for Arts and Culture and The Actors Fund offered significant contextual information in regards to copyright information of relevant dance & performance materials.

Photos by Yvette Ramirez

Yvette Ramírez is an arts administrator, oral-historian, and archivist from Queens, NY. She is inspired by the power of community-centered archives to further explore the complexities of information transmission and memory within Andean and other diasporic Latinx communities of Indigenous descent. Her archival practice is rooted in recordkeeping practices that embrace a hyperlocal and liberatory praxis especially when working with identity-related collections. With nearly a decade of experience as a cultural producer, Yvette has worked alongside community-based and cultural organizations such as The Laundromat Project, PEN America, Make The Road New York and New Immigrant Community Empowerment. Currently, she is an MSI candidate in Digital Curation and Archives at the School of Information at The University of Michigan and currently works at the University of Michigan Library’s Digital Preservation Unit.

Yvette Ramírez is an arts administrator, oral-historian, and archivist from Queens, NY. She is inspired by the power of community-centered archives to further explore the complexities of information transmission and memory within Andean and other diasporic Latinx communities of Indigenous descent. Her archival practice is rooted in recordkeeping practices that embrace a hyperlocal and liberatory praxis especially when working with identity-related collections. With nearly a decade of experience as a cultural producer, Yvette has worked alongside community-based and cultural organizations such as The Laundromat Project, PEN America, Make The Road New York and New Immigrant Community Empowerment. Currently, she is an MSI candidate in Digital Curation and Archives at the School of Information at The University of Michigan and currently works at the University of Michigan Library’s Digital Preservation Unit.

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.