By the Wallace Foundation Editorial Team

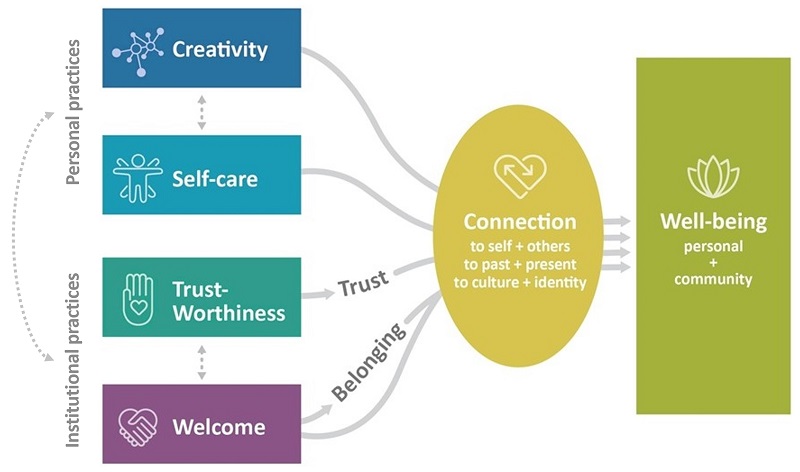

What kinds of arts experiences foster feelings of connection and well-being? A new report reveals some insights from Black and African American participants, a viewpoint historically sidelined from research and planning efforts in the arts. In-depth interviews with 50 Black and African American participants revealed common threads that demonstrate the importance of four key practices for arts and culture organizations in creating a positive environment: celebrating personal and community creativity, supporting self-care, working to be more trustworthy and creating a sense of welcome and belonging.

The qualitative study, A Place to Be Heard, A Space to Feel Held: Black Perspectives on Creativity, Trustworthiness, Welcome and Well Being, was funded in part by The Wallace Foundation, with research conducted in 2021. The project is part of a pandemic-era, equity-focused research collaboration with Slover Linett, LaPlaca Cohen and Yancey Consulting called Culture + Community in a Time of Transformation: A Special Edition of Culture Track. The initial survey research found that people crave more racial inclusion and connection from the arts, and a follow-up survey determined that people’s attitudes were shifting throughout the pandemic, with the desire for arts organizations to be more community-oriented only growing stronger. The new report homes in on perspectives from Black and African American participants, exploring how organizations can better support Black communities, work to earn their trust and make them feel welcome.

To examine some of the report’s key takeaways, the Wallace blog connected with the team from Slover Linett who co-authored the study (along with Ciara C. Knight): researcher Melody Buyukozer Dawkins, research coordinator Camila Guerrero and vice president and director of research Tanya Treptow.

Wallace Foundation: How did the four themes of creativity, self-care, trustworthiness, and welcome and belonging come into focus during the interviews?

Wallace Foundation: How did the four themes of creativity, self-care, trustworthiness, and welcome and belonging come into focus during the interviews?

Melody Buyukozer Dawkins: Our initial focus on the main themes of creativity, trustworthiness and welcome and belonging came from the first wave of quantitative findings from the Culture + Community: The Role of Race and Ethnicity in cultural engagement in the U.S. report. Those findings provided guidance at several levels:

- The findings indicated that Black and African American respondents were less likely to participate in the range of cultural activities included in the survey, even though those that did participate did so at the same frequency as the other racial and ethnic groups. One discussion our team had was whether the list of activities that we included in the survey was comprehensive enough to cover all potential activities Black respondents participated in. To this end, we took an open-ended approach in our interviews and asked participants about the general creative activities they partake in to expand this list.

- Over three quarters of Black and African American respondents desired change in arts and culture organizations and it was particularly important for them to engage with diverse voices and faces, more than any other racial and ethnic groups. About one third also wanted to see friendly approaches to diverse people. To examine in our interviews what dynamics come into play in these processes, we explored welcome and belonging.

- Black and African American respondents were also more likely than other groups to want to stay informed with trustworthy sources of information, so building on this finding we aimed to explore the factors that affect the trustworthiness of any organization or person.

We initially didn’t seek to examine self-care within our interviews but as we spoke to people, this theme emerged organically, especially as people talked about how they have been living through the pandemic era.

WF: Against the backdrop of the larger Culture + Community study, why was it important to conduct this qualitative study to gain the perspective of Black and African American participants regarding community and culture organizations? What are the benefits and tradeoffs or pitfalls of conducting research that delves deeper into understanding the experience of a particular group?

MBD: This is a question we heard often throughout both the research and dissemination process. One way we found very helpful to answer this question is to take a system-level approach and ask ourselves why the question of the importance of Black perspectives really exists in the first place. What structures and conditions that historically excluded Black people make this kind of research necessary? And why do we try to assess what there is to gain (or to lose) from this kind of research, rather than focus on how research can shift our paradigms and help us transform? With our research, we intentionally tried to stay away from the impulse to justify, but instead to amplify and celebrate Black voices, stories and wisdom, authentically and unapologetically.

Tanya Treptow: And we felt like a qualitative study could be an important complement to—and a check on—the quantitative components of the Culture + Community work. In qualitative research, we’re inherently not looking to generalize research findings, but instead to hear people deeply as holistic individuals and to understand the emotional undertones of people’s values, philosophies and actions. In this case, we were able to explore how culture and community experiences and organizations naturally fit into people’s broader lives.

Tanya Treptow: And we felt like a qualitative study could be an important complement to—and a check on—the quantitative components of the Culture + Community work. In qualitative research, we’re inherently not looking to generalize research findings, but instead to hear people deeply as holistic individuals and to understand the emotional undertones of people’s values, philosophies and actions. In this case, we were able to explore how culture and community experiences and organizations naturally fit into people’s broader lives.

WF: What most surprised or had an impact on you while working on this study?

Camila Guerrero: These were the first qualitative interviews I’d been a part of at Slover Linett and the loose structure of the interview, paired with people’s openness, seemed to create a space for vulnerability. The extent of how vulnerable people were willing to be, to talk about certain experiences they’d gone through was unexpected, because we were strangers and they didn’t owe us their unfiltered emotions, thoughts or experiences. The space we created in these interviews was safe not just for the participants, but also for us, the researchers. The interviews almost felt like a conversation I’d have with a friend even though they were for the purposes of this study. They all started off with “how are you feeling?” and despite our guiding question we still went in whatever direction felt most natural and comfortable. Each conversation brought something personal and eye-opening about the individual. One of many of those moments that still stands out to me is when one participant shared a beautiful moment of connection she had with her late mother through nature. I felt myself tearing up as she described her experience, and although perhaps at first glance it may have seemed unrelated to the themes we focused on in this study, it all circles back somehow. That very personal moment she gave us the privilege of exploring was what ultimately led to her love for photography, just one of the many ways she engaged with art.

Camila Guerrero: These were the first qualitative interviews I’d been a part of at Slover Linett and the loose structure of the interview, paired with people’s openness, seemed to create a space for vulnerability. The extent of how vulnerable people were willing to be, to talk about certain experiences they’d gone through was unexpected, because we were strangers and they didn’t owe us their unfiltered emotions, thoughts or experiences. The space we created in these interviews was safe not just for the participants, but also for us, the researchers. The interviews almost felt like a conversation I’d have with a friend even though they were for the purposes of this study. They all started off with “how are you feeling?” and despite our guiding question we still went in whatever direction felt most natural and comfortable. Each conversation brought something personal and eye-opening about the individual. One of many of those moments that still stands out to me is when one participant shared a beautiful moment of connection she had with her late mother through nature. I felt myself tearing up as she described her experience, and although perhaps at first glance it may have seemed unrelated to the themes we focused on in this study, it all circles back somehow. That very personal moment she gave us the privilege of exploring was what ultimately led to her love for photography, just one of the many ways she engaged with art.

TT: I definitely agree with Camila. I’ve been referring back to our conversations in professional contexts and in my personal life to a much greater degree than in other studies I’ve been a part of. I think it’s because of the open-ended framing of our conversations, where people could share what was most meaningful to themselves. In a lot of social research in the arts and culture realm, research is constrained to a somewhat narrower frame, such as attendance or participation at specific kinds of institutions. In this case, we didn’t constrain our conversations, yet as in Camila’s example, people naturally still shared stories about the arts and culture in their lives.

WF: Where do you think there are more opportunities for this kind of research and what would be a future priority from your perspective?

MBD: Shifting paradigms and building community. Thanks to the deep insights of our participants, we were able to examine the distinctions between trust and trustworthiness, and between welcome and belonging; explore the role of creativity and self-care in individual and community well-being; and question what “relevance” really means in the context of cultural experiences. One of the exciting outcomes of our study was that for each of our four thematic areas—creativity, self-care, trustworthiness and welcome—there were revelations that led to potential paradigm-shifting approaches to commonly used terms and concepts when equity and inclusion are talked about. So, one potential future priority for me is to rethink how we approach these concepts and how we ask questions in the first place.

CG: This study felt more like it was about amplifying voices and perspectives than about serving institutions and organizations. I hope it encourages others to move more in this direction, to be participant-centered. Although much of the focus of this study was to support institutions through our findings, throughout the process we found ourselves thinking about the interview participants as not just the main focus, but the main audience for our report. During our debriefs as a team it came up time and time again, that we wanted this to be something all the participants could read through and understand, because their insights were what even allowed us to get to this point. This participant-centered approach is something I hope to see more of in studies because without participants we have no research, no findings, no ability to take action.

WF: What implications does this study have for the arts and culture sector more broadly?

MBD: When we started this process, we were thinking about the audiences for this report. As we went through our conversations and started to identify themes, it became very apparent that the findings and insights went beyond the audiences (cultural practitioners and funders) we initially thought about. So, we shifted our focus to the “culture and community” sector, very broadly defined to include not only cultural sector practitioners and funders but also organizations, activists, policy makers and anybody who connects personally with or connects others around culture and community. Excitingly, we have already started hearing reverberations of our findings for people across a wide variety of fields like higher education, creative placemaking, civic engagement and sociological research on places and participation—many of the areas that have been working to incorporate the arts in comprehensive community development. I think one of the next steps is to capitalize on these reverberations and build community around how these learnings can translate into meaningful change, action and also more questions and research.

TT: I think there also needs to be a continued reckoning in the arts and culture field in accepting, celebrating and ultimately financially supporting arts and culture organizations and initiatives that support deep extrinsic goals, such as individual and community wellness (getting beyond art for art’s sake). Arts organizations that promote these goals explicitly are sometimes given less prestige than those focused on the quality of their collections alone. And that runs contrary to what we heard from the people we spoke to in this study in how they valued arts, culture and creativity in their lives.

We didn’t frame conversations around self-care or wellness, but these topics emerged anyways in very central ways. And I think this intersects with how the field should value and support BIPOC-led and BIPOC-centered organizations, which may be more likely to take an ‘arts and…’ approach. We do already see encouraging shifts in the sector, such as with John Falk’s 2021 publication, The Value of Museums: Enhancing Societal Well-Being, but there is so much more to do. I’d love to see continued centering of individual and community-level wellness at conferences, in the framing of funding opportunities and within individual organizational practice.

The included chart is excerpted from the study, A Place to Be Heard, A Space to Feel Held: Black Perspectives on Creativity, Trustworthiness, Welcome and Well Being. Images are courtesy of Slover Linett Audience Research and The Wallace Foundation.

This article originally appeared on The Wallace Foundation website. It is reprinted here with permission.

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.