By Bethany Greenho

Bethany Greenho is a 2023 Archiving and Preservation Fellow with Cleo Parker Robinson Dance. Read more about the Fellowships here. This is the fourth part of Bethany’s blog; read the third part here.

Making the Inventory Work

As with any archival project, working to inventory and begin organizing the Cleo Parker Robinson Dance (CPRD) archival collection came with its challenges. Most of these challenges were due to external factors, particularly the limited timeframe of my Fellowship as well as the space limitations in CPRD’s home, the Shorter A.M.E. Church. One challenge in particular that stemmed from these factors was not being able to conduct a full physical arrangement or organization of all the AV or manuscript materials. CPRD’s AV and manuscript, paper, and photographic materials were spread across eight physical spaces in the Shorter A.M.E. Church, meaning similar materials were separated from each other. While it would have been ideal to gather all of the manuscript, paper, and photographic materials into one space, organize similar materials together, and then inventory those materials, having no archives-only, secure location to work and only thirteen weeks for my Fellowship made that implausible. Instead, I chose to inventory and organize materials based on the box materials originally came in, a decision that initially seemed more difficult and less likely to fit CPRD’s wants and needs.

- Various A/V materials as they were originally found in one of the spaces in the Shorter A.M.E. Church.

- VHS tapes grouped together from the same CPRD-produced conference and with similar content

However, reading Matthew Richardson’s article “In Praise of Inventories” and looking at dance and performing arts organizations’ finding aids at other archival institutions provided a path forward. In discussing how Richardson and his staff use inventories at the Texas Medical Library’s McGovern Historical Center (MHC), Richardson mentions that they often don’t do a physical arrangement of the collections because they can find what they or researchers need using the inventory. When they do want to do a physical arrangement, the inventory is key to streamlining that process. With Cleo’s desire to have similar materials in the same physical space, Richardson and the MHC’s general approach to physical arrangement would not work with CPRD’s archive; however, the article was a reminder that the inventory could be used as a way to group similar material that could then be easily found and physically arranged together. This approach made inventory fields such as the “contentType,” “performanceType,” and “relation” fields even more important as these were ways the descriptions could group materials into categories to make it easier to gather and group material together in a box once the inventory was more complete.

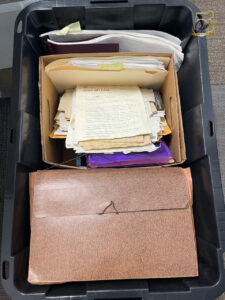

- A plastic tub filled with architectural plans, a document box of loose materials, and an accordion folder as they were originally found in CPRD’s Main Office closet.

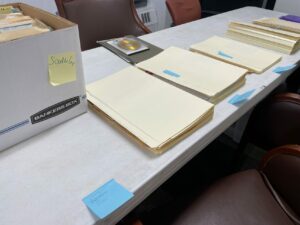

- The same manuscript and paper materials placed in archival folders and grouped in piles. Materials here are grouped into the series Repertoire Files, Production Files, and Touring Files.

The reminder provided by Richardson’s article was extremely helpful to me while inventory and organizing CPRD’s AV materials box by box. I felt more overwhelmed with how to organize the manuscript, paper, and photographic materials box by box than I had with the AV materials. It was in this overwhelmed state that I found different finding aids for dance and performing arts individuals and organizations. These included the finding aids for the Katherine Dunham papers, the Allan Grey Family Personal Papers of Alvin Ailey, the Oscar Hammerstein II collection, and the Martha Graham Dance Company collection. Initially, I looked at these finding aids to determine the terminology that other archival organizations used when describing dance, dance organizations, and performing arts collection materials as a jumping off point for the terminology I could use in the CPRD inventory. However, these finding aids were also helpful for organizing the manuscript, paper, and photographic materials. Each finding aid has sections titled “Scope and Contents” and “Arrangement,” which describe a collection’s series, or how materials in that collection are organized, and what kinds of materials are grouped together. These sections provided different examples as to how I might organize the manuscript, paper, and photographic materials in CPRD’s collection, which meant I did not have to reinvent the wheel. Instead, using these finding aids as examples meant I could copy or adapt the series to fit the CPRD collection materials and the needs of CPRD staff. For example, when going through and inventorying one storage tub that included production materials for annual concert performances and tours, choreographic notes, and honors bestowed upon Cleo Parker Robinson, I came up with the following series: Touring Files (copied from the Martha Graham Dance Company collection finding aid), Production Files (adapted from the Katherine Dunham collection finding aid), Repertoire Files (adapted from the Oscar Hammerstein II collection finding aid), and Cleo Awards & Honors. I would look at a folder of material, determine the series in which the materials best fit, and then write the name of the series on the left-hand side of the file folder tab. These series helped immensely in taking the initial chaos of many folders and turning it into a clearly defined system that at some point down the line could be easily used to identify and physically group together materials.

Screenshot from the CPRD Archive Inventory Procedures for Paper, Photographs, and Objects.

I should also note that having an understanding of how Cleo and other CPRD staff members organize and search for their day-to-day files and archival materials also helped me to organize materials in a way that made sense in both my box-by-box plan of organization and for a later, collection-wide physical arrangement. Asking them what the easiest access point is for the different kinds of materials, such as performance videos, tour itineraries, or promotional materials, or asking to look at how CPRD’s current digital files are organized also influenced how I organized archival materials. For example, within each series or within each box of AV materials, I would organize repertoire files and performance footage alphabetically by concert or repertoire piece title while touring files were organized alphabetically by tour city. Knowing these access points ensures materials are organized in a way that makes sense with how CPRD staff members think and conduct their operations.

These resources and information helped me work through one of the bigger challenges I came across during my Fellowship. Ultimately, this challenge and the solution I implemented was a great reminder that archival work is and should be iterative and that each archive is going to look slightly different. While I did not leave CPRD with a textbook image of archival boxes of perfectly physically arranged materials, I did leave them a system that worked within the limitations of this summer, fit with CPRD’s needs and organization, and, hopefully, is a system that other individuals working with the archive can easily understand and add to as the CPRD archive continues to take shape.

Header image: photo by Jerry Metellus, courtesy of Cleo Parker Robinson Dance Ensemble.

All other images courtesy of the author.

Bethany Greenho (she/her) is finishing a master’s degree in library and information science with a focus in archives and digital curation at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is interested in discovering how user-oriented access and ethical and community-centered description can become the means through which hidden or ignored stories become findable and accessible.

Bethany Greenho (she/her) is finishing a master’s degree in library and information science with a focus in archives and digital curation at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is interested in discovering how user-oriented access and ethical and community-centered description can become the means through which hidden or ignored stories become findable and accessible.

Bethany’s work with the George Balanchine Trust showed her the importance of having access to the tangible artifacts of dance as a way to preserve dance and its history beyond its ephemeral nature. In her current work with the University of Maryland Libraries Preservation Department, Bethany has seen how preservation works in concert with archives to ensure continued access to all stories.

Bethany is excited to use her background in dance and archival science at the Cleo Parker Robinson Dance Company to begin the process of organizing and preserving their collections to make them accessible to the community. Photo courtesy of Bethany Greenho.

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.