By Amy Schofield

Amy Schofield is a 2024 Archiving and Preservation Fellow with the National Institute of Flamenco. Read more about the Fellowships here. This is the third part of Amy’s blog. Read the second part here.

Archivo De Uso

One of the goals of my Fellowship this summer at the National Institute of Flamenco (NIF) was to begin conducting oral histories with NIF staff and community members who hold long-term institutional and artistic knowledge. I was already aware of some of the flamenco elders in Albuquerque because a few years ago, as part of the 2022 Festival Flamenco Alburquerque (1), NIF held a roundtable discussion panel on which Albuquerque flamenco elders recounted their careers and reminisced about the ways flamenco in the community has shifted yet remained a part of their lives. Witnessing these artists, one of whom was NIF founding director Eva Encinias, talk about their flamenco memories with such clarity and joy was an unforgettable experience, and I was excited to get in touch with them.

A photograph I took as an audience member at the June 2022 roundtable discussion panel that featured longstanding members of the Albuquerque flamenco community.

As I prepared to conduct the oral history interviews, the first step was identifying who we wanted to speak with. Many names I recognized came up. Marisol also mentioned her aunts and uncles, Eva’s siblings who had, like Eva, studied with Clarita, their mother. Annie D’Orazio, NIF’s Operations Director, sent out preliminary emails to those on our list explaining the archiving and oral history project and inquiring about availability. Some got back to us quickly, while others required a few nudges.

Annie and I had numerous conversations about where the interviews should be conducted, and we agreed that the narrator (interviewee) should select the location where they would feel the most comfortable. We also talked about the inherent power shifts and imbalances when there are cameras recording, and we contemplated the implications of recording the interview with both video and audio versus audio only. We also discussed how much of a presence we, as the interviewers, wanted to have in the final recordings. Ultimately, we wondered: How do we allow narrators to feel seen, comfortable, and in control?

Meanwhile, I got to work preparing a list of procedures, a release/informed consent document, and a few questions to get us started. I followed the lead of 2021 Dance/USA Archiving and Preservation Fellow, Yvette Ramirez, whose Fellowship included designing an oral history project within their community archiving project with DanceATL. Using Yvette’s materials as a guide, I created a procedures document that includes tips for technical elements, constructing questions, following up, and ultimately adding the interview materials to the archive. The informed consent document I created includes a description of the larger archiving project and explains to narrators their rights and responsibilities.

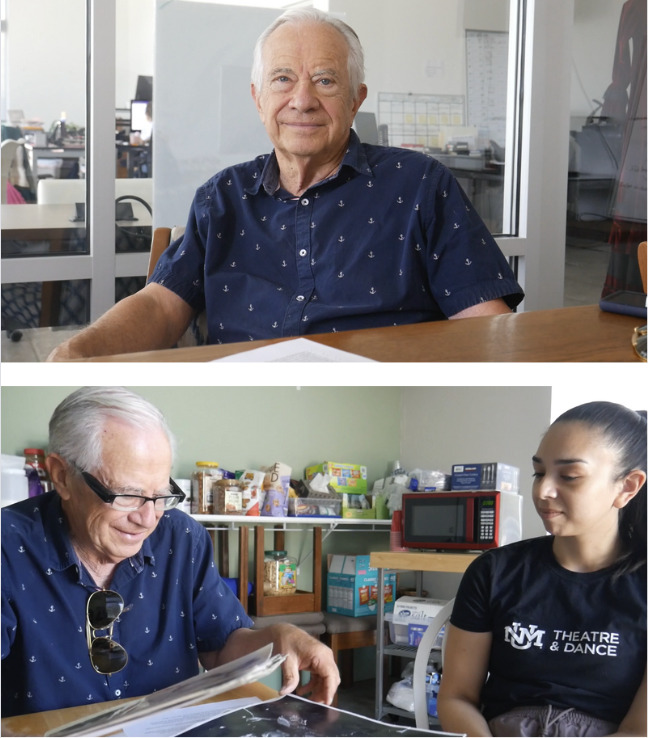

Our first interview happened just two days later, but we were ready! The camera was charged, we had extra batteries and SD cards on hand, and our documents were finalized. The first interview we conducted was with master guitarist, composer, and teacher John Truitt, known sometimes by his stage name Juanito. Since he has been there so many times over the years, John opted to do the interview in our office at NIF.

Performance review and images from the very first Festival Flamenco Alburquerque written by Teo Morca in the Summer 1987 issue of Jaleo: The Journal of the Flamenco Association of San Diego (vol. 10, no. 2). Digitized archival material courtesy of the National Institute of Flamenco.

John arrived early, and I developed a rapport through talking about the archiving project and showing him some of the newspaper clippings from the 1960s and 1970s about Clarita, with whom he performed for many years. I had never met John before the day of the interview, so Annie and I conducted the interview together. The comfortability and trust that was already established between John and Annie created a relaxed and casual atmosphere. Every so often, she would interject with a follow-up or clarifying question that stemmed from her deep institutional knowledge gained during her many years working at NIF. I was happy to have her in the room.

John talked a lot about his early career, and Annie and I were shocked by how sharp and specific his memories were as he described performances and conversations with exquisite detail. Afterwards, Annie and I discussed that there were a few points at which we found ourselves getting emotional while listening to John recount his flamenco memories. He spoke of the Encinias family with a huge amount of respect and reverence. Though the archive and his students are a reflection of the impact he has had on the Albuquerque flamenco community, he spoke of his own flamenco career humbly. Toward the end of the interview, I played a video from the very first Festival Flamenco in 1987, in which John performed. It was great to see him reminisce and watch videos of himself and his colleagues from almost 40 years ago. I also showed him the photographs from Eva’s house that I mentioned in my previous blog post. These archival materials spurred more stories and memories from John that wouldn’t have come up if not for his handling of them. John’s memories add a vitality and human touch to the archive, and he told us more than I can ever include in the notes of an inventory spreadsheet.

Stills from John Truitt’s recorded oral history interview. Images courtesy of the National Institute of Flamenco and used with the permission of the narrator.

I’m looking forward to conducting more oral history interviews with Albuquerque-based flamenco artists who have long-standing relationships with NIF. Our conversation with John got me thinking about the ways history is archived in the memories and bodies of community members. This Fellowship project is about the National Institute of Flamenco and the Encinias family, but it is also about the larger Albuquerque flamenco community. The U.S. southwest is a region with a complex story that contains the aftermaths of Spanish colonialism, the deeply rooted presence of Indigenous cultures, the political and economic pressures of Latinx US-American assimilation, and more. Queer feminist Chicana philosopher Gloria Anzaldúa would call this region a “Borderlands,” a geographical and metaphorical space of cultural, social, and psychological multiplicity, ambiguity, and hybridity. Anzaldúa frames the Borderlands both as a place of conflict and as a transformative and productive space of creation (2). This can be clearly seen in the flamenco produced in Albuquerque, and I’ve personally witnessed it in live performances by local artists. But how can this Borderlands flamenco be reflected in the archive?

Through the valuing of personal memory and story—and the ways they are shared in community—we are working to establish an archive that is enlivened by the voices and memories of community members. Flamenco scholar Cristina Cruces-Roldán defines “flamenco de uso” as the private everyday practice of flamenco in intimate settings, as opposed to flamenco that is intended to be seen in public performance (3). Critic and scholar Estela Zatania adds that flamenco de uso is practiced for the personal satisfaction of those who do it, rather than as a product to be sold and consumed (4). Flamenco de uso is based in community, in sharing, in what it does for the people who do it. Perhaps the archive we are creating at NIF may be considered an “archivo de uso,” an archive whose purpose and function lies in how it gives back to and sustains community and is based in intimate, familial, and community memory, support, and cultural stewardship (5).

Citations:

- The festival purposefully uses the city’s original Spanish spelling. The extra “r” in “Alburquerque” is intended to connect the event Spanish heritage and flamenco in the city.

- Anzaldúa, Gloria. (1987) 2012. Borderlands/ La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books.

- Cruces Roldán, Cristina. 2014. “El Flamenco como Constructo Patrimonial: Representaciones Sociales y Aproximaciones Metodológicas.” PASOS: Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 12(4): 819-835. Read it here.

- Zatania, Estela. 2019. “Perspectivas del baile flamenco en España y el extranjero.” ExpoFlamenco. December 4, 2019. Read it here.

- Marisol Encinias brought up the idea of “flamenco de uso” at the recent Dance/USA Archiving and Preservation Fellowship convening in Detroit, MI, which got me thinking about this idea.

Header image: Eva Encinias with her company Ritmo Flamenco. Photo by Douglas Kent Hall.

All other photos courtesy of the author unless otherwise specified.

Amy Schofield (she/her) is a doctoral candidate in Dance Studies at The Ohio State University. She is a flamenco dancer, scholar, educator, and choreographer whose research explores the development and evolution of flamenco in the diaspora. Her dissertation analyzes the ways Latinx flamenco artists in the US can use their flamenco practice and performance as a decolonial praxis that mobilizes and reinterprets the percussive artform to reflect and serve Latinx communities. Amy holds an MFA in Dance from the University of New Mexico and a BFA in Dance from the University of the Arts (Philadelphia, PA). She has studied flamenco extensively in Spain and the US, and she regularly teaches and performs with U Will Dance Studio, The Flamenco Company of Columbus, and Caña Flamenca in Columbus, OH.

Photo credit: Elliot Archuleta

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.